An entertainment reporter from the Daily Telegraph was recently looking for stories when she spotted that Australian influencer Skye Wheatley had been posting social media videos about receiving the skin treatment Rejuran. This led the journalist to begin questioning whether TGA guidelines prohibit influencers – or anyone – from promoting Rejuran, which is a cosmetic procedure.

While the journalist is right that the TGA does have very strict standards around the advertisement of certain procedures, she incorrectly conflated restrictions around Schedule 3, 4 and 8 drugs and certain procedures with restrictions regarding all cosmetic treatments. Posting a positive video about your experience with a product or treatment – even if it’s not a paid ad – is still considered an advertisement by the TGA, however f you were to check, you’d see that Rejuran doesn’t contain a prescription-only medicine, so the product itself isn’t prohibited from being advertised to the public.

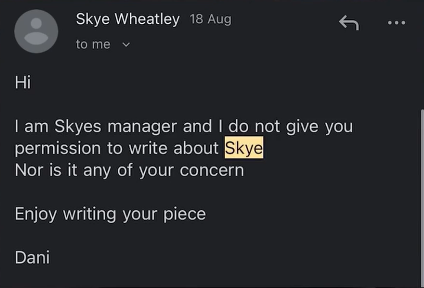

But that’s not what I want to focus on. It’s Skye Wheatley’s manager’s response to the journalist’s enquiry. Why? Because it made me think, “if only PR was this easy.”

I do sometimes wonder if some of the potential clients we speak to think that getting a journalist to cover a story – or, in this case, not cover a story – really is as easy as Wheatley’s manager makes it out to be in the above email. Looking at this, you would think issues management is simply a matter of speaking to our media buddies and asking them not to report on something, or offering to do them a favour in exchange for taking a certain angle or turning a blind eye to an issue.

But, as the fallout shows, it’s really not that easy.

The right way to handle media enquiries

If I were in the habit of representing influencers – which I’m not – what would I have done differently in this situation?

Firstly, I would check with an expert to see if my client really was in the wrong. If they weren’t, as seems to be the case in this scenario, I would share that factual information about what the TGA stipulates and how my client is not in breach of any restrictions with the journalist. I would not, under any circumstances, respond with aggression, sarcasm, or anything that indicated irritation, defensiveness or superiority.

I would also make it clear that my client is careful to adhere to the TGA requirements and is grateful that the TGA requirements exist because they support consumer safety and encourage the right information for anyone who’s interested in different types of treatments.

After sending the background information on the TGA requirements, I’d organise to have a friendly chat with the journalist over the phone to allow space for them to share (unprompted and without giving them any ideas) any other angles they may have been wanting to pursue in order to nip it in the bud and hopefully address any misconceptions. This alone can result in their ideas becoming non-stories, while at the same time ensuring the journalist sees us and the client as transparent, helpful and professional.

Sometimes you can’t stop a story, but you certainly can minimise the damage or correct any misunderstandings. And a friendly collaborative approach is often the best way to do this. After all, you catch more bees with honey.

Being defensive or combative actually creates a bigger story, even if the journalist’s enquiry isn’t based on truth or is unfair. As we’ve seen in this instance, it can provide fuel for another story entirely – potentially one that has a bigger reach and negative impact than the original story. While Wheatley wasn’t in the wrong originally, her manager’s unprofessional response has cast her in a bad light after all.

And if you want another example of how an arrogant response to the media is received, just ask Qantas this week.

And that’s what’s noteworthy in PR this week.